When the Sierra Club announced last fall that they were inviting their community to share their art and creativity to help collectively grapple with the climate crisis and imagine a future with a Green New Deal, we thought that was quite extraordinary. Not exactly known for being a beacon of cutting edge cultural hipness, it seemed significant that an environmental organization as big and established as they come would look to random flashes of inspiration for a way forward on the most daunting ecological challenge humanity has ever faced.

In fact, when digging a little deeper to find out more about the genesis of the creative showcase, it turned out that Chelsea Watson, the organizer of the campaign, had grappled with that same bigness. “As a relatively new organizer at the Sierra Club, the largest grassroots environmental organization in the United States,” she wrote, “I struggle to grasp what our size of 3.5 million members and supporters really means. Numbers are big, nonprofits love them, but I often have difficulty really feeling their significance.”

Through a mobilization last summer called “Growing the Green New Deal” that had the Sierra Club community meeting with their members of Congress about upcoming climate and clean economy legislation in order to sow the seeds of the Green New Deal, Watson — a recent Yale Environmental Studies graduate with a focus on justice and a passion for creativity — began to understand “the abundance of knowledge, creativity, and power that exists within this big messy network of humans.”

One fun, plant-based twist they had thought of struck a particular chord: asking the thousands of activists engaging in the mobilization to bring vegetables, fruits, flowers or other offerings to the nearly 100 lobby meetings across 22 states to symbolize the growth they were asking for not only left an impression with lawmakers but brought out each participant’s unique experiences, visions for the world, and roles to play in the movement. The outpouring of all that creative energy and all around positive feedback was a clear sign that this type of creative work was something they needed to do more of, and thus the Green New Deal showcase was born.

As the submissions of everything from paintings to posters, sculptures to screenplays, songs and dances (over 150 in all!) were being posted on the Sierra Club’s social media pages, Tao the GND Editor-in-Chief Sven Eberlein was getting deeper into a dialog with Watson about how the project came about, what it took to put it together, and what lessons might be learned from it, both for the Sierra Club and the broader Green New Deal movement.

In true concert with the Green New Deal’s crucial tenets of inclusion and participation, Watson kept stressing how much of a collaborative effort the entire showcase had been, giving props to her intrepid co-creators, Destiny Hodges and James Ousman Cheek, who were interning through the Sierra Club’s Healthy Communities and Labor and Economic Justice programs at the time. Both students at Howard University, their shared interest in using creativity to address environmental inequity was the perfect match for Watson’s vision. And the rest, as they all whole-heartedly confirmed in our interview a few weeks later, was history.

The goal was to add some life and spirit and creativity and opportunity for self-expression in something as intimidating and difficult as a lobby visit with a congressional rep and their staff.

What we didn’t anticipate was just how far beyond the artistic showcase the conversation would go. While the interview took place pre-COVID and the worldwide Movement for Black Lives uprisings, the themes that came up were poignantly prescient in their holistic assessments of remedies needed to address the intertwined crises of human and environmental equity. After two hours on Zoom, it had covered everything from the new black arts movement’s inherent embrace of natural elements to the need for an intergenerational and intersectional approach to bringing about systemic change.

Looking back at that conversation now, it feels like it was both a lifetime ago and just yesterday. A lifetime because the ground underneath our feet has shifted so drastically in the last few months that it’s hard to remember what it was like before. Just yesterday because the fundamental work we need to do toward a just transition remains the same. On the latter, it’s good to remind ourselves that the task of creating both new narratives and policies is not starting right now, it’s just intensifying.

For this current moment of potential for deep transformation to become possible, enough people had to first lay the groundwork by reimagining the old and outdated stories entrenched in our collective consciousness. Honest conversations, creative activism, and tireless advocacy had to ripple through homes, communities, and public forums for years, so a growing collective understanding of the underlying systemic injustices and inequities could be strong enough to harness the shocks of witnessing an old system in its most raw and brutal failings into inflection points for a sea change.

Now that the floodgates of attention have been opened and the call for justice and equity is finally sweeping across every geographic and cultural region of America like water seeping into a parched desert landscape, ideas that the current civil unrest is deeply connected to the racial disparities exposed by the coronavirus crisis, every environmentalist should be anti-racist, or that you cannot stop climate change without ending white supremacy, are finally allowed to be self-evident. The fact that the Sierra Club’s recent announcement to face its own white-supremacist history seems nothing more than par for the course is a stunning tribute to just how fast the ground has shifted under our feet. Rise in Power, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, David McAtee, Ahmaud Arbery, and all the other Black lives that were cut short at the hands of police.

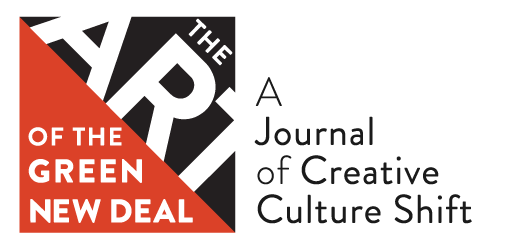

This brings us back to why creativity and the Green New Deal are more relevant than ever. With the idea of a just transition at its core, the Green New Deal’s principles of equity and change are not only at the center of what the times are calling for, but by their very nature depend on our imagination to envision a world that does not yet exist. As Destiny Hodges says at one point in the conversation, “art is a way to bring people together collectively, art is all encompassing, art is a form of expression, a way to activate social change. So quite honest, the Green New Deal is art.” The creative Green New Deal state of mind, in fact, may be uniquely untethered to imagine that now is the time for a Black New Deal.

The following excerpt of the exchange should give all of us a lot of confidence and hope that the transformations as outlined in the Green New Deal Resolution are well on their way in the hearts and minds of a generation poised to take the tiller in rapidly shifting political winds.

Day 1: It’s Time for a Green New Deal

Sven Eberlein: Tell me a little bit about yourselves. How did you meet? When and why did you first decide to advocate for a Green New Deal? How did you get involved with the Sierra Club?

Chelsea Watson: I got my start as an organizer with the fossil fuel divestment movement. I’m also passionate about creative projects and get a lot of joy from them. In my position now as a distributed organizer for the Resist campaign, I organize volunteers across the country through online to offline actions. A lot of what I do is to create a pathway for the tens of thousands of folks who have called their members of Congress to go do an offline or an in-person action, whether it’s going to mobilizations like the climate strikes or having an in-person lobby visit with their member of Congress. It’s a creative mix of digital communications and organizing work generally, so when the Green New Deal came up, we were able to lend support, along with our Healthy Communities and Living Economies campaigns, because the nature of the Resist campaign is that we work on the opportunities and threats of the Trump Administration.

Destiny Hodges: I got involved with the Sierra Club when I met Larry Williams Jr. (Labor and Coal coordinator of the Sierra Club Labor and Economic Justice program) at a Congressional Black Caucus Green Room event. He said, you know, I would love to help any young black professionals who are also interested in going into the environmental field. So when I was looking for internships I asked him if there was anything available at Sierra Club. I told him that I was coming from a journalistic background and wanted to use media as a form of narrative organizing to pursue my mission of educating and uplifting the stories of marginalized communities impacted by environmental inequity. I was only a freshman in college, so I wasn’t really eligible to apply for most internships that I wanted, but he said, let me see what we have going on. So they opened up an intern position under Healthy Communities, which is Sierra Club’s fusion of labor/economic and environmental justice.

So Ousman and I — who both go to Howard University but we didn’t know each other — got together at the internship, and it turned out that we have a lot of similar views and thoughts. We’re both creatives, we’re both Tauruses [laughs], so we just kind of hit it off. Working really easily together, we identified a lot of things that we saw from a different perspective of being creatives and of being college students entering a big green organization that probably a lot of people didn’t. Or that we later saw they did, but because of their capacity and job descriptions they didn’t have time for things like using art as a way to advocate for the green New Deal. And then we met Chelsea.

James Ousman Cheek: For me, the entry into Sierra Club was similar to Destiny’s. We actually met Larry at the same event. I’ve always done visual art and I used to sing when I was a kid— weirdly enough [laughs]. I’d say I’m an interdisciplinary artist, which I think makes sense given my interdisciplinary academic focus (Cheek studies Environmental Studies with a Japanese minor)., I came into Sierra Club in the labor and economic justice program and then through the Healthy Communities project that was focused more on community organization based interventions.

It was a good introduction to community organizing because I’ve been feeling this angst of wanting to work with the people who are most affected by these environmental concerns, people within my community. I was actually struggling with the idea of coming in and telling people what is best for them. So we were exposed to some of the organizing principles that encourage the community to dictate their own needs like the Jemez principles, and that whole experience really opened my eyes to how to actually go about helping people. But within whatever role I’m in, I always like to be able to do something creative, so when I heard that Chelsea was doing this project I just wanted to talk to her.

Instead of calling all artists we were calling all creatives. You'd be surprised. We didn't just get art. We got films. We got songs. We got everything and it's all art and that's the main thing this was about.

Sven: So how did the project start?

Chelsea: As I mentioned, a lot of what I do is lead mobilizations for in-district lobbying visits. So in the summer, we tried out a creative twist on how we can have people talk to their member of Congress about the Green New Deal and other clean energy or climate bills that might be seen as a step forward in that direction. So we created a mobilization called Growing the Green New Deal with the idea that people would bring something as a symbol or an offering that represents growing this vision.

The goal was to add some life and spirit and creativity and opportunity for self-expression in something as intimidating and difficult as a lobby visit with a congressional rep and their staff. So by creating this opportunity — do you have flowers in your neighborhood that you want to bring? Are you a gardener? Are you an artist? — you can show up to this meeting in a way that feels special and unique to you, and it doesn’t have to all be about one person with a sheet of paper facing another person with the sheet of paper negotiating policy. That’s not what our activism has to be, and actually it can be a lot more powerful if there’s space for creativity and fun and new ways of thinking. For me, that was the most successful push for lobby visits I’ve had. With this creative push we had nearly 100 lobby visits across the country, whereas normally, you know, in my first couple of rounds of testing this out, we might get like ten.

Sven: Sounds like it really loosened things up and added a lot of humanity…

Chelsea: Yeah, absolutely. And just packaging it all together into a theme that people want to be a part of. It wasn’t just like, “please, be a lobbyist for us.” It was like, “this is a mobilization under this umbrella theme and these are fun ways you can participate in it.” There are also other factors, of course, like it’s the Green New Deal and it’s popular! But for me, it’s pretty clear that the creative human twist made a really big difference and a lot of people had a lot of fun with it.

Sven: So how did that turn into the Green New Deal showcase?

Chelsea: Originally I was hoping the showcase would be a simultaneous action option during August recess. We ended up focusing just on the lobby visits, but when I saw all of the outpouring of creative energy and got so much support and validation from my peers, I knew this type of creative work is something we needed to pay attention to and do more of. So when I got to meet with Ousman and Destiny, it had already been a dream of mine to connect it, and they had been thinking of similar things, as well. So it was a really clear alignment.

Another thing that I think is really interesting is that this was a really cool opportunity from an organizing perspective. We had this theory that there are probably a lot of people who feel like they want to be a part of the movement but feel like there’s no space for them. Not everybody wants to do a lobby visit and I think that is okay. So we saw this creativity from August recess and knew we gotta listen to this, but we also knew that there are a lot more people who are saying they’re interested but not signing up for lobby visits, so we wondered what will happen if we create this other space for more people to identify with this movement and raise their hand?

Day 2: What are we up against?

Sven: It’s like you were riding the momentum of that first campaign and finding ways to maintain it. So how did the art campaign come together from there?

Chelsea: Destiny and Ousman, you were there for a lot of the beginning of it. Do you want to hop in with some of our first processes for creating and launching it?

Ousman: Destiny and I realized very early on that within the field of environmental justice and community-based organization there’s a paucity of platforms that explain what it is conceptually and enable people to work on the interdisciplinary aspects of it. So we came up with an idea of a digital media campaign that humanizes modern environmentalism, how environmentalism is about trying to make sure that communities are not downwind from plants and lead smelters that cause increased rates of asthma. We realized that there needs to be a big media push for this, and with Chelsea moving into other aspects of her project like providing that platform for creatives who are not comfortable with approaching politicians directly, we thought about how we could harness the Sierra Club’s resources to reach a creative audience like us.

Destiny: Honestly, I think it was just a very genuine sit down. All three of us got together and just started talking about our backgrounds and our interests, which is how a lot of our conversations are [laughter]. When Chelsea mentioned that she was interested in doing a project such as this, I was like, this is absolutely perfect, because personally, I don’t identify as an artist. I’m a creative, so it’s very important to think about the words and the messaging that you use to attract different people. To me, art is any form of expression, but to someone else that might mean something different, so it’s very important to think about how you engage with audiences.

If we want The Green New Deal to happen, we need everyone to feel like they are and can be a part of the solution. It’s not going to happen on its own — we have to work together to make that happen.

So instead of calling all artists we were calling all creatives. You’d be surprised. We didn’t just get art. We got films. We got songs. We got everything and it’s all art and that’s the main thing this was about. I think Chelsea asked us what success with this project would look like for us, and I was saying that there are no metrics. There’s no numbers. It’s reaching one person and getting one person’s art out there. Getting one message out there, elevating someone else’s work. If it’s one person, that’s success to me. And with this project we had over a hundred and fifty submissions. It was more than that, by quite a bit…

Chelsea: I’m gonna maybe check right now to see what the numbers are… [laughter]

Destiny: Yeah, incredible. Honestly, I wasn’t extremely shocked, because I knew that the audience existed. it’s just that with Sierra Club, there weren’t that many communication avenues that they were using to grab onto that audience. So this is a very impactful way to do that. One of the things that we really wanted to focus on was to make sure the artists’ backgrounds aligned with the Green New Deal topics that we were asking for. The identity piece was definitely a thing because — just being quite honest — Sierra club’s audience is mainly older white people. Which is okay, but we wanted to make sure that we highlighted artists of all different backgrounds. There’s a film student who’s out in LA in college. Her perspective is different. There was someone that was bedridden and they felt that they couldn’t get out there and fight by foot, but just by showcasing and telling a message with their art they were still a part of the fight. There’s so many avenues of sharing a message that you can show with art, it’s incredible. Art is often used to convey a message and make people think about something more than just conceptually, but to actually visualize it and make it tangible. And that’s exactly what this is. especially with the Green New Deal. It’s taking all those bits and pieces and making it visible for someone, making it a reality.

Sven: Do you think campaigns like these can help shift the Sierra Club membership’s demographic makeup to include more communities that haven’t traditionally been included in their outreach? And could this creative approach provide a platform for these communities to lead on the issues most important to them?

Ousman: Absolutely!

Destiny: Actually, I’d say it’s important to acknowledge that it’s already going on. There are other spaces within frontline communities where a lot of creatives are already doing a lot of great things. They just don’t have a platform such as Sierra Club as an avenue to express. For instance, there’s Hip Hop Caucus, a platform a lot of artists already use, including pushing an agenda. But I think one of the things that we’re looking forward to with this project in the future is reaching out to other communities and audiences to bring them in and showcase their work. Because really, all we want to do is showcase their work and use it to advocate for the Green New Deal. That’s it. That’s the main goal.

The way we did it was we reached out to the base that already existed within Sierra Club, via email list and social media. And because Sierra Club’s demographics are what they are, that’s who you sent the message to. So that explains the content that we got and the demographics with that. But we are very much interested in reaching out to other audiences. Ousman and I even spoke of reaching out to our own personal networks of artists and creatives to say, hey this is going on, feel free to submit, because a lot of people we know already do the same things.

Day 3: Fighting for our future

Sven: So Sierra Club is open to transforming itself, so to speak, through these kinds of campaigns?

Destiny: Well, I’m not going to speak for Sierra Club as a whole [laughs], but I would say, absolutely, and that’s very present in the work that they do. Sierra Club is doing work in communities, and helping and providing resources to communities, rather than claiming them and their role in it. I don’t see why they would not want to use other avenues to engage the communities that they’re in.

Sven: And the equity aspect is such a big pillar of the Green New Deal, really, part of its DNA, right?

Ousman: Absolutely. I’d say it’s crucial for the long-term survival of the organization. I mean, the Sierra Club has access to a lot of young liberal progressives who are drawn to it and who are also tech-savvy. I think initiatives like ours are helping Sierra Club engage with an expanding audience. For a long time creatives weren’t necessarily leveraged within the movement, so administratively there aren’t always avenues to activate creative approaches and perspectives. But as we look at the long-term viability of the Sierra Club and other environmental orgs, I think that it’s crucial.

Something I’ve found that in the new black arts movement: there is an inherent embrace of natural elements. A lot of my friends emphasize natural elements in their art. One who is culturally Nigerian makes paintings of masked figures that are like spiritual avatars, but they exist in settings that are bonded with nature. It’s not overtly environmentalist, but at the same time it’s an expression of environmentalism through beauty. I have another friend who makes smoothies while he’s DJing [laughs]. Both of these forms of expression lean towards healthier, more sustainable lifestyles and perspectives, and I think it’s the most powerful way to use art to communicate environmental awareness, where an inherent appreciation for nature is implicit in the process.

Ultimately those are the things that shape people’s perspectives, right? If you have a lot of media that portrays people in opulence and pursuing luxury, then media consumers are going to want that. As we start to bring in creatives to translate these purely conceptual ideals, and people start to process and internalize how they fit within their lives and identities, a cultural shift becomes possible.

Art is a way to bring people together collectively, art is all encompassing, art is a form of expression. It’s a way to activate social change. So quite honest, the Green New Deal is art.

Sven: Is that how you approached the curating of your art submissions? You must have been flooded with tons of artwork and had to make some decisions. Did you come up with a guideline for which of these pieces you felt were most compelling or relevant to the showcase?

Chelsea: I can kick us off with that, but I want to say one more thing that’s coming up for me listening to this conversation. In order to make the Green New Deal a just, inclusive, and powerful Green New Deal, we need massive public movement, awareness, input, all of that stuff. That means way more people have to see themselves as a part of that solution. By having such an open call, a lot of our art may not look relevant to the Green New Deal to every viewer. For example, one piece was from someone who grew up in the Bronx, and they described it as “I grew up in an underfunded neighborhood, and when I think about the Green New Deal, I think about what it means for my neighborhood and for kids growing up in this neighborhood in the future.” Maybe from a white, more privileged environmentalist perspective that’s not the solution, but the point is, no, that is a solution, that is what the Green New Deal is. And someone DJing and making smoothies, that is the Green New Deal [laughs]. This is not just about, “oh, we love creativity and we are creative people and want to be a part of it.” This is also strategic because if we want The Green New Deal to happen, we need everyone to feel like they are and can be a part of the solution. It’s not going to happen on its own — we have to work together to make that happen.

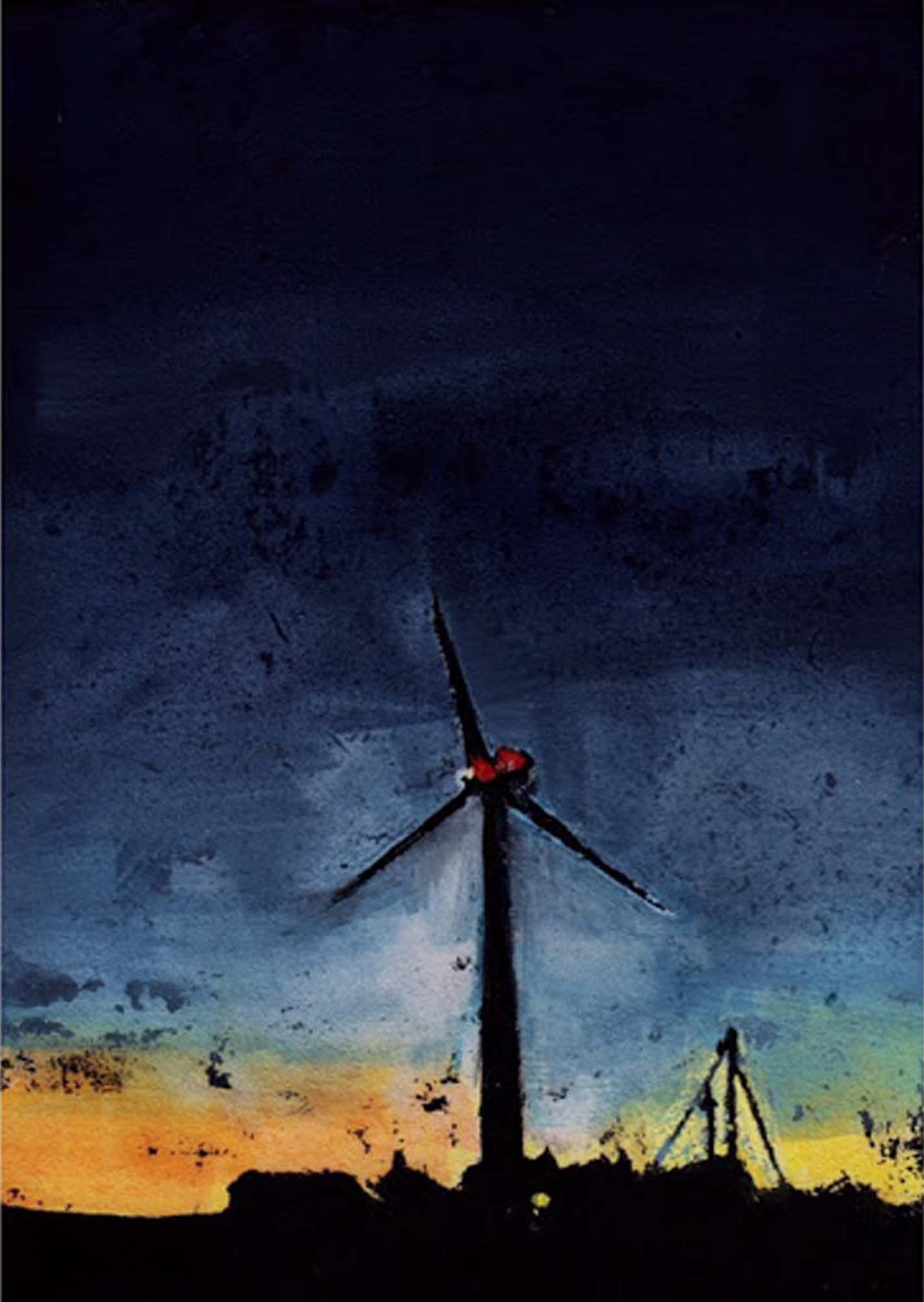

Sven: It’s almost like a creative survey so you can get an idea of how people relate to it. Like, what are the pieces that are going to speak to people and how do they envision their lives in it? It brings me back to the original New Deal, where they also put a lot of emphasis on things like the dignity of work. It wasn’t just about putting money in people’s pockets and to rebuild the economy, but about what are we doing as a society, what’s the higher purpose? What do we really care about when all is said and done? And speaking to your point, Chelsea, it’s not just about, “oh, here’s this great poster that says ‘Green New Deal’ and there’s a couple of windmills and a train in it.” Of course, those are good to have, too, but it’s almost cliché at this point. That’s why it’s really powerful to have pieces that don’t literally relate, to make people think about all the different realities and entry points, because now you have a survey of how people are coming to this.

Destiny: One thing though we need to make sure here is that the original New Deal isn’t idolized. It left out a lot of marginalized people and allowed labor unions to monopolize and then discriminate against people of color, especially the black community. And the way it dealt with farmers, with loans — there were just a lot of problems with the New Deal. Even though a lot of great things came out of, I just want to make sure that it’s not idolized.

But to your point about different realities and entry points, that’s one of the main things Ousman and I talked about even before we got up with Chelsea. We were like, well, we have this audience within Sierra Club and everybody has their own personal niche that they’re interested in, whether that’s polar bears, oceans, plastics, pollution — there’s so many different areas. But in order to have a Green New Deal, most importantly we need to realize the intersections of all of these things, that they all relate, and that we can solve all of them together. So the question for us was, where is somebody’s interest at and how can we connect them based on that interest to everything else, so they can see the whole picture? And that’s one thing that we want to do with this project and one thing that I think Sierra Club is trying to figure out — how can we use the audience and the platform that we have to make the larger connection? When you start that process of critical analysis, you cause people to question their own understanding, the understanding that society has, and where changes need to be made so that we can understand all our work collectively. And that’s exactly what you’re talking about.

Day 4: Energy Solutions

Sven: That’s really fantastic. And to your point about the original New Deal, it’s really important to us at TAO the GND to acknowledge and learn from the shortcomings of the original New Deal. Which leads me to the question of — with the experiences that you’ve had through this campaign and having digested things a bit — what do you think is the best way forward? Are there any plans to take what you’ve done to the next level?

Chelsea: There are a lot of things that I think will come out of this. This was our first launch, our initial gauge of what will happen if we go to our existing base. There are already a ton of wheels spinning and really beautiful work can come out of this, whether or not it’s within the same project.

I’ve also been thinking about what else we can do with all this amazing art we already have from these submissions, and this amazing pool of artists. Our DC office is going to buy some art for our office and I want to work with other chapters to buy art as well. So in addition to using the relationships we already have to make more connections and have art more integrated with all of Sierra Club’s work, there’s also other projects that have been kicked off because of this. I’m sure there will be more things that will come of it. I’m sure Destiny and Ousman also have some thoughts.

Moving forward, it’s not good enough to draw a landscape portrait to show natural beauty, if in the process you are using plastic paint, like acrylics that over time will contribute to the decline of the environment.

Ousman: Yeah. Well, since our internship is coming to a close in about a week or so, we won’t be able to be as hands-on with the next steps moving forward, but it’s really been an eye-opening experience for me. I have recognized that my role within the environmental movement might be leaning more creatively than I previously acknowledged. I’m really interested in dismantling why we think the way that we do right now and how we can use humanity to bolster our strengths that have allowed us to get this far as a species, instead of the weaknesses that have been used to prop up unsustainable systems throughout society and the world, you know, like trade, war, and consumerism’s many forms.

So there were a couple of projects I came up with earlier that were impossible due to financial and time constraints, but I’m interested in approaching other entities in DC about them. One project that incorporates art, specifically ceramic, is called Soil and Sprout. As a kid, I was really interested in claymation, like Wallace and Gromit, so I made a lot of little clay sculptures. Then I ended up doing ceramics in high school and again in college, and I realized it’s important to approach art with the idea that we need to reshape our approaches to a lot of things. Materiality is important. Moving forward, it’s not good enough to draw a landscape portrait to show natural beauty, if in the process you are using plastic paint, like acrylics that over time will contribute to the decline of the environment.

So let’s use the Earth and make sculptures that can actually promote growth. Think “a Chia Pet combined with a Grecian urn”. And from each of the pots you can grow plants that might be super effective at air purification. So I wanted it to be an interdisciplinary project where ceramic artists approach botanists, chemists and other life scientists on campus to say, “Hey, what are the best shapes I can use to promote the root growth of this specific plant, or what are the glazes I should be using that wouldn’t inhibit growth,” you know? So I’m interested in organizing projects that combine creative pursuits with more scientific or technical approaches that can elevate the creative expression.

Another project was a mural idea for DC. There are a couple of organizations that bring in muralists for projects and I wanted to do one that highlights community leaders. I’m going to go into these communities and ask if any members have made efforts toward environmentalism or natural living, even if they weren’t labeled as such. Say there’s an old lady “Ella Mae” who helped put together a community garden. We could put Ella Mae on the side of a building and let the community know that other people appreciate the work she did while encouraging more to follow her lead. And I also want to include a virtual or augmented reality aspect with an animation or a video over the mural of her tending the garden. And then there could be mural tours to promote it to people who seek out these little moments of community leadership, sustainability, and creative expression. So that’s where I’m headed now, and it’s absolutely because of this project.

Sven: That is such a beautiful idea.

Day 5: All Living Things

Ousman: Yeah. Well, since our internship is coming to a close in about a week or so, we won’t be able to be as hands-on with the next steps moving forward, but it’s really been an eye-opening experience for me. I have recognized that my role within the environmental movement might be leaning more creatively than I previously acknowledged. I’m really interested in dismantling why we think the way that we do right now and how we can use humanity to bolster our strengths that have allowed us to get this far as a species, instead of the weaknesses that have been used to prop up unsustainable systems throughout society and the world, you know, like trade, war, and consumerism’s many forms.

So there were a couple of projects I came up with earlier that were impossible due to financial and time constraints, but I’m interested in approaching other entities in DC about them. One project that incorporates art, specifically ceramic, is called Soil and Sprout. As a kid, I was really interested in claymation, like Wallace and Gromit, so I made a lot of little clay sculptures. Then I ended up doing ceramics in high school and again in college, and I realized it’s important to approach art with the idea that we need to reshape our approaches to a lot of things. Materiality is important. Moving forward, it’s not good enough to draw a landscape portrait to show natural beauty, if in the process you are using plastic paint, like acrylics that over time will contribute to the decline of the environment.

So let’s use the Earth and make sculptures that can actually promote growth. Think “a Chia Pet combined with a Grecian urn”. And from each of the pots you can grow plants that might be super effective at air purification. So I wanted it to be an interdisciplinary project where ceramic artists approach botanists, chemists and other life scientists on campus to say, “Hey, what are the best shapes I can use to promote the root growth of this specific plant, or what are the glazes I should be using that wouldn’t inhibit growth,” you know? So I’m interested in organizing projects that combine creative pursuits with more scientific or technical approaches that can elevate the creative expression.

Another project was a mural idea for DC. There are a couple of organizations that bring in muralists for projects and I wanted to do one that highlights community leaders. I’m going to go into these communities and ask if any members have made efforts toward environmentalism or natural living, even if they weren’t labeled as such. Say there’s an old lady “Ella Mae” who helped put together a community garden. We could put Ella Mae on the side of a building and let the community know that other people appreciate the work she did while encouraging more to follow her lead. And I also want to include a virtual or augmented reality aspect with an animation or a video over the mural of her tending the garden. And then there could be mural tours to promote it to people who seek out these little moments of community leadership, sustainability, and creative expression. So that’s where I’m headed now, and it’s absolutely because of this project.

Sven: That is such a beautiful idea.

I'm really interested in dismantling why we think the way that we do and how we can use humanity to bolster our strengths that have allowed us to get this far as a species, instead of the weaknesses that have been used to prop up unsustainable systems throughout society and the world.

Destiny: I think Ousman was touching on some really important elements as far as the interdisciplinary nature of environmentalism, sustainability and the Green New Deal, and it is very important to highlight that and to have other people realize within their own niches the connection of all of those. My hopes for the future of this project is to have it be multifaceted and grow into something that would expand on the definitions of things, recognizing that any form of expression is art. Maybe we could even have a film or a fashion aspect of that. Something I’m doing on campus currently — and Chelsea said it, yeah, I’m an organizer [laughter] — is organizing a whole bunch of students to do a whole bunch of things to change the culture of what sustainability looks like on this campus.

At Howard we have so many creative people and I’m a part of an organization called Models of the Mecca. It’s not only modeling, but photography, videography, there’s designers, makeup designers, it’s everything you can think of. I had a couple conversations with them as we planned a climate strike on campus, and I was like, “are you guys interested in environmentalism?” And they’re like, “you know, I don’t really think that’s something that…” And I’m like, “well, you design clothes and all of your clothes are solely thrifted and upcycled. That’s sustainable.” And they were like, “whoa, that’s true.” [laughs] So again, just realizing that that fits into the larger picture and that ultimately that is the Green New Deal, because the Green New Deal is art. Art is a way to bring people together collectively, art is all encompassing, art is a form of expression. It’s a way to activate social change. So quite honest, the Green New Deal is art.

Sven: Hey, that’s the title to this story right here. [laughter] So what tips do you have for others looking to add art and creativity to their Green New Deal advocacy and activism who might feel intimidated or don’t think it’ll make a difference?

Destiny: I’ll say that it’s very important to instill and realize the power that you have as a single person. Like Martin Luther King jr. said, for every person or every group of people who led a movement, it started with someone thinking something and realizing that collectively there were other people who thought like that. Whether or not they truly knew that other people existed who had the same sentiments, they existed and that when we come together collectively, things happen. And so that’s literally the same case with everything. If there’s something you as a person individually feel that matters, it matters and you’re not the only person who thinks that way. And if you might be one of a few people, you can use your story to help other people realize that there are more people and that “hey, this is me too.” So that’s the number one tip I would give to anyone, to really realize the power that you have and the power that art has. We are art. We create art. We embody art.

Day 6: Reused Materials & Eco Art

Sven: Do you all feel like it’s a burden that there’s so much emphasis on your generation right now as far as inspiring these changes because others couldn’t get it done before? Or is that a motivational factor, like “wow, it’s us, that feels good!” From just listening to you, it sounds like it’s a motivating factor to be thrown into the water and start swimming…

Ousman: I was actually thinking about this earlier and wanted to make sure I don’t communicate frustration. The emphasis gives the feeling that there is purpose in your action, like that energy has an outlet, you know? Just from going through life and realizing how imperfect things are, that is inspiring, because it allows you to be in a position where you say, okay, so let’s look at these systems really critically and think about why they are the way they are. Like, what was their foundation? What are their intentions for the future? You ask, “what are the best ways of going about that?” Adding different layers to say, “if we have this kind of social issue, what might that indicate as trends?” And then finding those trends and addressing them. So I feel like it’s been inspiring because it makes you investigate the sources of our issues and approaches to addressing those issues for fundamental change.

That being the case, my frustration has come from some people in older generations telling us that things are incapable of being changed. That “that’s the way things are.” In a world free of conditioning, nature prefers equilibrium, right? Nature tends to create systems that can sustain themselves. The fact that our constructed system has us careening into oblivion [laughs] is clearly an indication that we should (and could) have better options, right? So taking that into consideration, this really is an opportunity to do better and to try to harness all of the marginalized communities, identities, and perspectives that have so long been kept down. We need those comprehensive perspectives. We need that indigenous knowledge. We need those alternate ways of sustainable living. We need all of that in order to create best practices that we can all pick from. There’s no group that has all of the answers and it’s imperative that we bring people in to get a universal scope of how to address these issues.

Chelsea: I have a really clear response to that. Since I was a child I knew there was something wrong with older generations saying you are going to change the world. Like, you are not dead yet! [laughs] Why are you telling me this eight-year-old is going to change the world when you are a fully adult person who has a much bigger position of power? So I think the “oh look at the young people, they’re making the change” is actually a really problematic mindset. I’m not the first person to say this, but a common narrative for many young leaders right now is, “no, by the time it would take one of us to get into a position of power to make these decisions, it’s too late.” So it’s definitely not just on younger generations to be doing this.

The positive side of this, I guess, is that at least there is some acknowledgement of youth leadership right now. For example, this project was totally bottom up, like, we came up with this project and we got approved and we were able to get the support to do it. So it’s cool that we are able to step into leadership in all different ways and spaces, but it is unfortunate that sometimes we have to feel like we’re the only leaders. And there are many leaders from different generations. Our elders are amazing and they should definitely be respected for that. The mindset that the younger generation is a solution… maybe it’s true, and I wish that was not the only truth out there.

Destiny: I share the same sentiments. For me it’s frustrating because yeah, we didn’t create this mess, so why do we have to clean it up? I’ve heard that a lot and that’s real, but also, I know that I’m here right now and I know that I’m going to make a difference. All my friends are like, oh you’re trying to save the planet, and I’m like, well, the planet could take care of herself, it’ll continue long after we’re gone. I’m trying to save people, and I know that every day we continue to operate out of these systems, more and more people are affected and will be affected disproportionately. And so I take a personal responsibility as someone being here and present. I have a duty to make sure that we don’t continue to go down this treacherous path because people will continuously be hurt.

And quite honestly, people that look like me will be hurt at a disproportionate rate. And that hits home for me.

One thing I’ve been talking about and I see spurts, especially with the youth climate strike movement, is that it takes an intergenerational approach. It is not just us, by any means. We have the motivation and we’re here right now and our voices are loud and we’re really doing the work. But it takes the wisdom and experience from people who have been fighting the good fight, because they have been here and they still are here fighting. In combination with us, our will, our creativity, our new views on things, and our willingness to change the systems. Because honestly, we haven’t been in the systems as long as older people have to get as discouraged. So it takes that combination to really make a difference and I hope that more people are able to see it like that, because I feel like it is just really irrational to solely place the change of our world on our generation of people. That just makes no sense.

People hate to hear this, but I feel like if you are here in this present moment, you have some type of responsibility to humanity because we are all humans and we all are naturally social animals that depend on each other to do things, to shape our behavior the way that we live, the way that we are. We naturally have a responsibility to change these systems, to change this world, if you want to continue to live in it. And it’s not just on me as a young person. It’s not just on my generation. It takes a holistic approach which means identifying and acknowledging other perspectives and including them. And it takes the knowledge and the wisdom of everyone who’s already been here. Even if they’re not older, because there are some young people who are really wise and experienced. It takes a combination of all of our experiences, all of our perspectives, all of our backgrounds, and all of our identities to really make something possible.

Ousman: I think the thing about us being social animals is that one person’s change in perspective has the potential to ripple through personal networks and then society. As that person moves, the knowledge shapes their behavior and can bleed out onto others. I think if we keep using these multifaceted approaches, we can meet people on that “one thing” they need to be pulled into the environmental movement. Once we do that we can really start shifting the needle, because the necessary changes happen on the population level, but individuals make up that population.

Day 7: Our Social Movements

Sven: Well, you all are certainly giving me a kick in the pants to recommit! You know, what happens when you’re at this for a long time, sometimes you just get tired and complacent, and then so it’s really good to get that new burst of energy. And you know, a bit of shaming never hurt anyone [laughter]

Chelsea: I hope it didn’t come out as shame…

Sven: Not at all. You know, for me personally, that’s pretty much what my entire life has been dedicated to, so I always try and think of what else I could be doing. But there are limits as to what one person can do, right? And it’s counterproductive to beat yourself up. That’s when people go into despair, and we don’t want to be in despair because that’s completely paralyzing and then we’re not doing anything. So you have to keep your righteous anger but channel it into parts of the solutions.

For me, one of the ways of dealing with it all, having known for a long time how bad things are, has been to not be too attached to the outcome. Like, you do the work you do because you believe that’s the right way. You keep your eye on the question, how do we want to live together? How do we want to live in balance with this planet, which we know we have to be in order for things to be restorative and for the natural systems to be functioning, right? And you do the best you can for yourself and to inspire others, and you do it with love in your heart.

It sounds kind of cheesy, but I think it also motivates because there’s a human element underneath it all, even though we’re talking about greenhouse gases and the physical environment. Ultimately, it’s about how we want to live together. And so I derive great energy and inspiration from what all of you are doing and all the other people who are getting engaged in whichever ways they can, whether it’s the small things in your own home, getting involved in your community, or getting on a more national or global platform. There’s so many different ways. So that gives me energy to keep going without ever despairing. We’re here now and let’s do the best we can, you know?

Destiny: I feel like a lot of people limit themselves by this “it sounds cheesy” sentiment, but there really is no limitation unless you create the limitation for yourself. And yes, the limitation you create might be shaped by society and bureaucracy and a plethora of things, but there’s no real limitation unless you create it for yourself. That’s one of the things that I realized at a young age, that I have no limitations. There are only people’s limitations that have been created for me, but I have no limitations. So anything I aspire to do is possible. Same thing goes for any and every one, and once you realize that, anything is possible.

Sven: Thank you for that reminder. And thank you all so much!

Pingback:We can be whatever we have the courage to see | The Art of the Green New Deal

Posted at 16:22h, 04 September[…] […]