Sometimes it’s truly uncanny how synergistic human consciousness can be. I’ve always thought that the world as it exists is the result of what we collectively dream into being, and if a lot of people dream the same thing at the same time, this dream and all its interconnected threads is bound to rapidly and visibly manifest in the waking world.

Still, as comfortable as I consider myself to be with such sublime convergences, I admit that it threw me for a galactic loop when Congresswoman and Green New Deal resolution co-author Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez recently tweeted “a very special + secret #GreenNewDeal project” announcement mere minutes before I sent the draft of the creation story you’re about to read to my collaborating editors.

“Holy cow,” I thought to myself. “A creative Green New Deal storytelling project! This is exactly the kind of stuff we’ve been building our hub for.” When the surprise — a beautiful, visionary video entitled A Message From the Future With Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez — was revealed the next morning, I was stunned by how much the storyline, the visuals, and the aspirational nature of this moving piece of contemporary art fit into what we’d been dreaming up over the last several months.

The Art of the Green New Deal

The idea for some sort of a creative hub that would turn the hapless U.S. president’s iconic paean to selfishness and greed into a playfully subversive ode to possibility and regeneration had initially come to me during a weekend in the woods in November 2018. It began to take real shape during a Green New Deal Create-a-thon a month after the resolution had been released. During a weekend of collective brainstorming, we fleshed out the framework for The Art of the Green New Deal as a journal of creative culture shift that would collect and chronicle the creative endeavors in support of the adoption and implementation of the Green New Deal.

One of the many common threads between A Message from the Future and our vision for the journal are the references to the art programs that flourished during the original New Deal era. In Naomi Klein’s clarion call accompanying the video, she not only muses that a Green New Deal could “galvanize artists into that kind of social mission again,” but that the time to crank up the turbines of inspiration is in fact right now, because we’ll need all artistic hands on deck to “help win the battle for hearts and minds that will determine whether it has a fighting chance in the first place.”

Speaking of Naomi Klein, I can’t help but wonder if she was writing those lines at the exact moment I added the quote about the ethos of care and repair from her previous Green New Deal article to this story (see below). Also, did we somehow tune into the wavelength of the Message from the Future crew when we came up with a Letters from the Future column during the create-a-thon?

Whether it’s all providence I’m not sure, but with all the existential social, economic, and environmental challenges we’re facing on this planet it seems significant that so many of the same powerful ideas are suddenly bubbling up from sea to shining sea. And The Art of the Green New Deal, in a nutshell, is poised to catch the most beautiful, diverse, and expressive of those bubbles that tell the stories of how a Green New Deal will help transition our nation into a society that lives within Earth’s carrying capacity and where everyone can thrive.

A showcase for the creative human engagement needed to bring about the shift, the idea is to start The Art of the Green New Deal as a well curated online journal. From photo essays and creative non-fiction to video, audio and media yet unseen, it will stream the resolution’s various interconnected pillars — from clean energy and sustainable food systems to social/economic equity and community resiliency — through the portals of Works, Movements, and Narratives.

What’s the big (Art of the Green New) Deal?

For those of us who have been tuned in to the magnitude and urgency of climate change for a long time, House Resolution109 — Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal — has come as a much welcomed solution befitting the scale of the problem. Laying out the goals, aspirations, and specifics for the United States to create the economic and societal transformation needed to meet the International Panel on Climate Change’s targets to avoid the most irreversible impacts of global warming, the non-binding document introduced by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.) has led to a seismic shift in our collective imagination of what’s considered possible.

Thanks to the spirited activism of the Sunrise Movement, a diverse coalition of young activists, the Green New Deal has now entered the public lexicon in the same way the original New Deal etched itself into the American imagination long before its first programs were enacted. Against all conventional wisdom, Sunrise succeeded in creating the kind of irresistible moral tipping point that has made it attractive for a broad cross-section of political candidates and lawmakers to get behind this ambitious vision. And proving just how broad-based the hunger for a bold approach to climate action is among the American public, the baseline for support of almost all its key ideas stands at over 80%.

Just as FDR’s ambitious reforms were criticized from both the right (socialism!) and the left (fascism!) at the time and took years of political battle to come to fruition, the road to the Green New Deal will also be a long and winding one. Even at this early visioning stage, long before any actual legislation has been proposed, the very concept of systemic change is facing stiff headwinds, from the strategic (e.g. U.S. Senate procedural show vote) to the absurd (Cow farts! Bye bye hamburgers! Have more babies!). If there’s one thing we can be sure of it’s that the Green New Deal will be an epic battle for the hearts and minds of the American people, and by extension, the votes of their elected representatives.

And herein lies the The Art of the Green New Deal. In order to cajole the political majorities needed to adopt the policies designed to jumpstart the programs that will set in motion the infrastructural transformations at the heart of a post-carbon society, we need to function at the highest levels of aspiration. Beyond the duty-driven (and plain sensible) motivation that we shouldn’t be burdening future generations with life on a planet heated to extinction levels, we must invoke stories and imagery that speak to our imagination if we are to create a collective consciousness on par with and supportive of the monumental physical tasks at hand.

There is a grand story to be told here about the duty to repair — to repair our relationship with the earth and with one another, to heal the deep wounds dating back to the founding of the country. Because while it is true that climate change is a crisis produced by an excess of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, it is also, in a more profound sense, a crisis produced by an extractive mindset — a way of viewing both the natural world and the majority of its inhabitants as resources to use up and then discard. I call it the “gig and dig” economy and firmly believe that we will not emerge from this crisis without a shift in worldview, a transformation from “gig and dig” to an ethos of care and repair.

- Naomi Klein

The questions, thus, can not only be about how much it is going to cost and who is going to pay for it, but how do we want to live together. What do we as individuals and in our communities value most in our limited time on this planet? What gives our lives meaning? Far from just a human interest side bar in the feature story about budgets, technology, and jobs, addressing our deepest human longing and greatest motivations is the inner portal through which we not only see and perceive the external world but influence and change it.

Past is prologue

And here too we can look to history for inspiration. The importance of the human spirit was certainly not lost on FDR and his New Deal architects who intuitively knew that the ambitious employment and infrastructure programs they were developing under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to address the crisis of their time — a ravaged economy driven by grotesque wealth disparities, with over half of all Americans trapped in poverty — weren’t just about putting money in people’s pockets but about restoring human dignity, belonging, and confidence. “Happiness lies not in the mere possession of money,” Roosevelt proclaimed in his first Inaugural Address in 1933. “It lies in the joy of achievement, in the thrill of creative effort.”

Far from being a mere platitude, the social value of creative effort was deemed vital enough to warrant its own comprehensive arts program under the WPA, Federal Project Number One, informally shortened to Federal One. Conceived and administered by Harry Hopkins, a former social worker who had become one of FDR’s most trusted advisors, Federal One’s five divisions — the Federal Art Project, the Federal Music Project, the Federal Theatre Project, the Federal Writers’ Project, and the Historical Records Survey — were based on the (not so) radical notion that not only should artists have the right to public employment and compensation like any other worker but that the arts should be considered just as valuable to the common good as business, agriculture, or labor.

“I don’t know why I still hang on to the idea that unemployed actors get just as hungry as anybody else,” Hopkins reportedly jabbed as he recruited director and playwright Hallie Flanagan to head the Federal Theatre Project. Before long, painters and sculptors, musicians and composers, actors and stagehands, and playwrights and writers all around the country were applauding their good fortune to be remunerated for expressing themselves freely and compiling a remarkable archive of cultural contributions while doing so.

If these kinds of deeper connections between fractured people and a fast-warming planet seem far beyond the scope of policymakers, it’s worth thinking back to the absolutely central role of artists during the New Deal era. Playwrights, photographers, muralists, and novelists were all part of a renaissance of both realist and utopian art. Some held up a mirror to the wrenching misery that the New Deal sought to alleviate. Others opened up spaces for Depression-ravaged people to imagine a world beyond that misery. Both helped get the job done in ways that are impossible to quantify.

- Naomi Klein

Wanted: A Just Transition

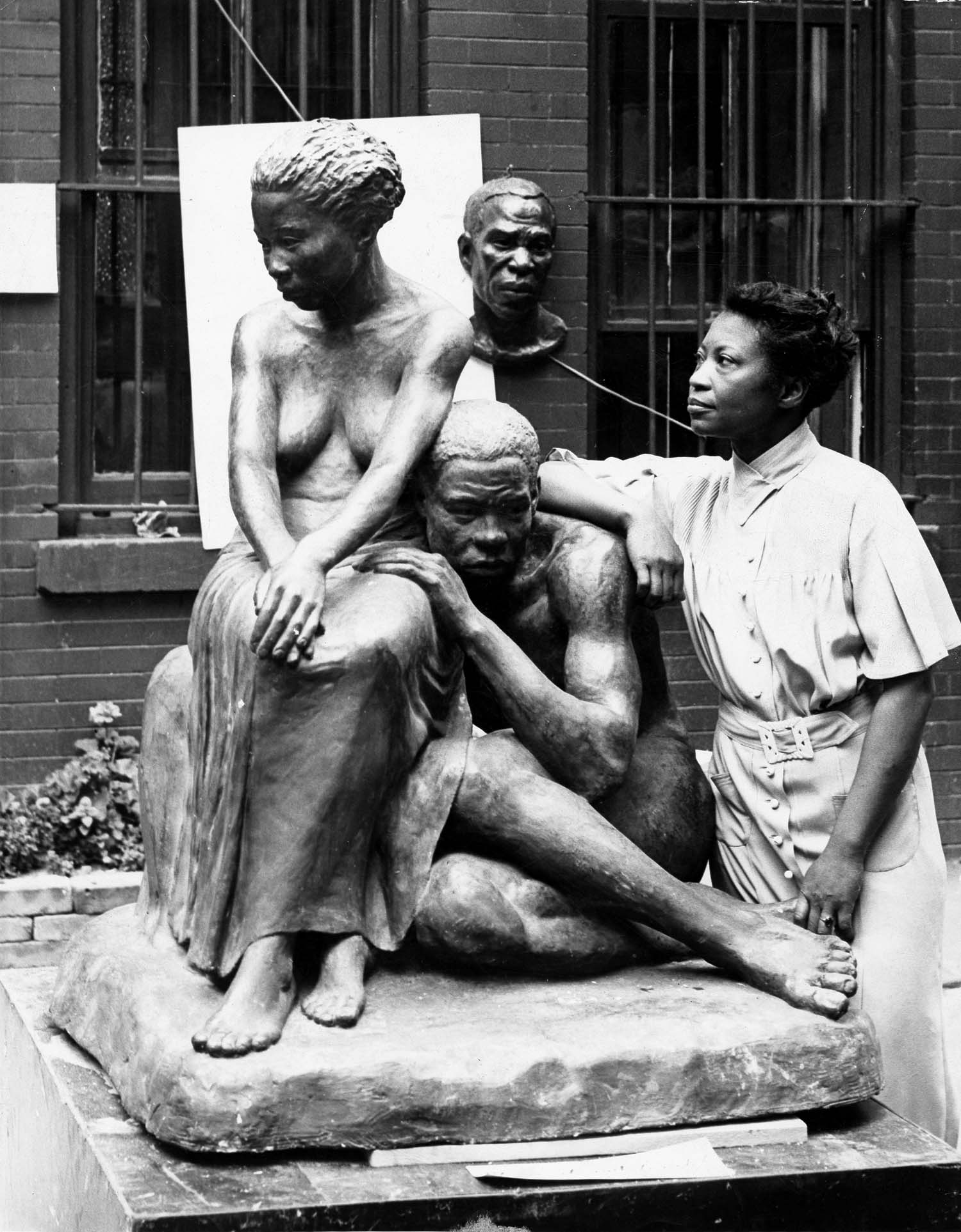

In addition to the obvious parallels we can draw between the 1930s and today in terms of looking to the work of our creative citizens to guide us through a seismic societal realignment, there is one other aspect in particular of the WPA’s arts programs that renders them even more relevant to the ideals espoused in the Green New Deal resolution: their distinct lack of the racial prejudice that was otherwise a feature throughout New Deal programs.

As has been rightfully pointed out since the idea of a differently-shaded New Deal entered into our current public discourse, most of the original New Deal projects were steeped in the systemic racism of the time and available to white men only. While perhaps more by necessity than by design due to the votes of racist Southern Democrats Roosevelt had to rely on to enact his economic relief programs, this New Deal hallmark of discrimination perpetuated already well-entrenched racial and gender disparities and further cemented the socioeconomic and its related environmental injustices that persist in America to this day.

By contrast, thanks in large part to African-American artists in New York City who formed the Harlem Artists Guild to protest the discriminatory practices and successfully pressured the WPA to hire an unprecedented number of Black artists, Federal One stood out as remarkably unique for its diversity. With color lines removed, Black artists for the first time were able to practice their art full time and become equal members of a community fighting for equal rights for all artists. Federal One also hired Native American, Chicano, and Asian American artists in a time when they were excluded from most commercial jobs, providing not only badly needed income but the opportunity to tell their stories in their own voices. The fact that the Federal Theatre Program was headed by Hallie Flanagan speaks volumes, but women were also represented throughout Federal One as writers, actors, and muralists.

It comes as no surprise then that the Green New Deal authors, cognizant of history’s lessons that exclusion and discrimination are anathema to the very concept of vibrant and sustainable coexistence, went to great lengths to enshrine a “just transition” into the resolution’s blueprint:

(1) it is the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal —

(A) to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions through a fair and just transition for all communities and workers;

(E) to promote justice and equity by stopping current, preventing future, and repairing historic oppression of indigenous peoples, communities of color, migrant communities, de-industrialized communities, depopulated rural communities, the poor, low-income workers, women, the elderly, the unhoused, people with disabilities, and youth (referred to in this resolution as “frontline and vulnerable communities”);

- H.Res.109 — Recognizing the duty of the Federal Government to create a Green New Deal.

The resolution’s heavy focus on making sure everyone benefits equitably from the envisioned transition should put the “past is prologue” spotlight squarely on Federal One, as it is the one New Deal program that most closely presents a working model for Green New Deal advocates, policy writers, and eventually, administrators. As the Creative Action Network, a community of artists that is taking design inspiration from original WPA posters to create Green New Deal art, puts it, “for today’s Green New Deal to succeed, we need to learn from what worked before, and it’s clear that nothing worked better than having diverse artist voices front and center.”

In addition to serving as a model for how to inject a strong sense of fairness and togetherness into any emerging Green New Deal projects, the visionary contributions of the WPA artists — in spirit and in works — make a compelling case for the inclusion of a modern equivalent arts program for the Green New Deal. For if we are to genuinely transform our cities, towns, economies, and energy and transportation systems into less or non-extractive entities as rapidly and drastically as science demands we must, we will need all the inspirational stories, evocative installations, and kick in the pants performances we can get.

Deal us in

And this is where the journal comes in. As mentioned earlier, The Art of the Green New Deal aims to be a showcase for the creative human engagement that will be needed to power a shift in collective cultural consciousness commensurate with the scale of the proposed structural and societal transformations.

As the journal evolves, it may become a go-to library of quality creative assets that could serve as project proposals for any future Green New Deal arts program, and even the basis for a print journal, films, tutorials, workshops, or other yet unimagined educational resources in service of the cause.

Ambitious? Yes. But this moment in history asks all of us to stretch our perceived limits beyond what we think possible.

For “if civilization is to survive,” as Franklin Delano Roosevelt so wisely proclaimed during his last address to the American people, “we must cultivate the science of human relationships — the ability of all peoples, of all kinds, to live together, in the same world at peace.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.